Zoonotic diseases are diseases that can be transferred from animals to human beings or from humans to animals.

Humans can act as carriers of the diseases and spread them as well as be affected and die in case of the more serious ones like Anthrax, Brucellosis, Rift Valley Fever, Tuberculosis etc.

Introduction

Domestic animal diseases present problems not only for their handlers, i.e., farmers, but also for consumers when animals are used for food. Food products made from animals include not only meat, but meat derivatives that are added to sweets and other foods, and therefore, are less obvious to consumers.

An example of a disease believed to be transmitted to humans from an animal product is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease-variant (vCJD), of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), also known as "mad cow disease". Despite the extreme rarity of this illness, the effects are so devastating that public health officials around the world recommend their governments take strict prevention measures (CDC/Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.)

The following animal diseases are known to affect humans in one form or another:

- Anthrax

- Bovine Farcy

- Brucellosis

- Hydatid cysts

- Influenza - avian flu, swine flu etc

- Leismania

- Leptospirosis

- Mad cow disease

- Mange

- Orf

- Pseudo cow pox

- Q fever

- Rabies

- Rift Valley Fever

- Ringworm

- Salmonellosis

- Taeniasis - tape worms

- Tetanus

- Toxoplasmosis

- Tuberculosis

Bovine Farcy

Scientific name: Bovine nocardiosis

Read more under Skin problems

This is a bacterial disease caused by Nocardia farcinica organisms. These organisms cause chronic, non-contagious diseases in animals and humans. They are commonly found in soil, decaying vegetation, compost and other environmental sources. They enter the body through contamination of wounds or by inhalation. Only cattle and humans are affected.

The disease in cattle is characterised by infection and swelling of the superficial lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes of the legs, neck and around the base of the ears.

It appears initially as small nodules under the skin, most often on the legs and on the neck, at the base of or near the ears. The nodules develop slowly, and some are grouped together in the form of a large mulberry. They are firm and painless. Swellings may persist for years with no apparent adverse effect on the health of the animal.

A veterinarian will confirm the diagnosis by smears of pus removed from an unopened abscess. The main concern is to distinguish the lesions of Bovine Farcy from those of Tuberculosis, which on occasion it can resemble, especially when there are internal lesions, such as those occurring within the chest cavity.

Brucellosis

Common names

Contagious abortion, Bang's disease, In humans also called Undulant fever and often confused with malaria or influenza

For complete description please see: Reproductive Problems

Brucellosis is a bacterial infection, caused by organisms belonging to the genus Brucella.

The disease is prevalent in most countries of the world. It primarily affects cattle, buffalo, pigs, sheep, goats, camels and dogs, and occasionally horses.

The disease in humans, sometimes called Undulant Fever, is a serious public health problem, especially when caused by Brucella Melitensis.

Brucellosis in cattle is caused almost exclusively by Brucella abortus, although occasionally Brucella melitensis or Brucella suis may be implicated. Melitensis occurs primarily in sheep and goats; suis in pigs. Brucella canis is confined to dogs.

Cattle of all ages and sex can be infected with B. abortus,but it is primarily a disease of sexually mature female cattle, with bulls and immature animals showing little or no clinical disease.

Spread to man

- Man becomes infected when in direct contact with cows at abortion, calving or in the post calving period.

- Vets and stockhandlers are particularly at risk from the splashing of infected droplets into the eye.

- Handling of the afterbirth without wearing gloves is very dangerous. Afterbirth of infected animals should be buried immediately and not handled directly by anyone.

- Infection occurs in people drinking unpasteursied milk or milk products.

- Symptoms in humans include recurrent bouts of fever, headache, muscle and joint pains and and general weakness. Women also abort. Brucellosis is often confused with malaria and influenza. Diagnosis is done through a blood sample taken by the doctor, and treatment is usually a very expensive 3 month on antibiotics

Diagnosis

This is based on the history, serology and bacteriology. Abortions occurring after 6 months of pregnancy are suggestive. However, blood samples should be taken for detailed laboratory analysis to confirm the disease.

- Serum samples should be taken for agglutination testing.

- When abortion occurs, aborted fetuses should be taken intact in a sealed container to the laboratory for detailed examination. The organisms can be found in the placenta but more conveniently in pure culture in the stomach and lungs of an aborted foetus. All foetuses and afterbirths should be handled carefully with gloves to avoid human infection.

Diseases with similar symptoms Abortion: See Vibriosis, Leptospirosis, Rift Valley Fever

Prevention - Control - Treatment

Prevention and Control

- The disease can be controlled through effective sanitary measures in the cattle environment. Pregnant animals must be closely observed and any which show signs of aborting must be immediately isolated.

- Any animal which has aborted must be kept isolated until all uterine discharges have stopped. If there is any suspicion of infection, any animal about to calve should also be isolated.

- Under cool conditions the organism may survive for up to 2 months. Exposure to direct sunlight kills the organisms within a few hours.

- The use of plastic gloves and thorough disinfection of the vulva and tail of cattle helps greatly to reduce the risk of infection when examining pregnant animals.

- Because of the danger of human infection, infected fetuses, placenta and cows should be handled with great care. Proper hygienic precautions should be taken when handling abortions and where infection is known to occur in certain herds of cattle. Handlers of such material should always wear gloves for protection. They should also ensure that they keep their hands away from the mouth, nose and eyes until after the hands are thoroughly disinfected.

- Burn or bury all contaminated materials such as foetuses and foetal membranes

- Clean and disinfect all cattle premises which may be contaminated with foetuses and foetal membranes.

- Drinking of raw milk and unpasteurized milk products should be prohibited

- Pasteurisation of milk and milk products makes them safe for consumption.

Vaccination

- Calves between three and eight months should be vaccinated with live vaccine (S.19) to prevent infection. Such vaccinations can provide lifelong immunity against all but the heaviest challenge.

- The live vaccine should be used with care in adult animals because it can cause abortion in in-calf females and inflammation of the testes in adult males. It also results in persistent antibody titres if used in adults, making differentiation between antibody levels due to natural infection and vaccination very difficult Adult cattle should therefore be vaccinated annually with dead B. abortus vaccine (45/20), or a with a reduced dose - one twentieth - of S19 vaccine.

- S19 vaccine should be handled with care. It is a live vaccine and can infect humans.

- Vaccination will reduce the number of infected animals in a herd by by over 90% if carried out over a period of 5 years. Vaccination cannot eradicate Brucellosis but it can lay the groundwork for future eradication.

- Bulls should not be vaccinated as the vaccine may result in the organism appearing in the semen.

Recommended treatment

Brucella infections are known to be persistent, so treatment of animals with antibiotic is not recommended. It is therefore not practical and not useful to make any treatment attempt. Infected animals should be culled. Meat is safe for consumption if cooked well.

Hydatid cysts

Hydatid cysts: Echinococcus granulosus

Hydatid cysts are unfortunately not uncommon in human beings. Mature cysts can reach up to half a meter in diameter if not attended to. A person may look very pregnant only to find out that what they have is a hydatid cyst, which will have to be removed surgically.

This is a very short dog tapeworm, whose main significance is that the larval stage forms large multiple hydatid cysts in the intermediate hosts, including humans. These cysts are located in the liver and lungs and can grow to a very large size indeed. People living in close association with dogs are especially at risk

Influenza - Bird Flu - Swine flu

(under construction)

Leishmaniasis

For full datasheet please link to Human Health/Insect transmitted diseases (under construction)

A skin disease of humans and in other parts of the world - dogs. In Africa it is mainly transmitted by sandflies, and dogs seem to be less affected.

Lizards, rodents and rock hyraxes are intermediate hosts.

Leishmaniasis is caused by protozoal parasites of the genus Leishmania, which were originally parasites of rodents, in which they cause a mild skin disease. They are transmitted by sandflies and have become adapted to dogs and to man in whom they cause three main clinical types of disease.

- Skin (Cutaneous) Leishmaniasis.

- In some parts of the world the infection may spread to the lymph nodes, other areas of skin and to mucocutaneous junctions- this type is called Espundia or Lymph node (Mucocutaneous) Leishmaniasis.

- The final type is one in which spread occurs throughout the body and this is called Visceral (affecting soft internal organs) Leishmaniasis or Kala-azar. The name Kala-azar derives from Asia and means "black fever" and refers to the darkening of the skin which may occur in fair-skinned people, when they contract Visceral Leishmaniasis.

Leptospirosis

Introduction

Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease caused by members of a single species. Leptospira interrogans, which contains two major groups - those which are free-living and those which are strictly parasitic.

Domestic animals, wildlife and humans can all be infected.

Most infections are subclinical, but severe disease characterized by haemolytic anaemia leading to jaundice (pale yellow gums, underside of eyelids etc), blood in the urine, and sometimes death, or milder forms with fever, milk drop, atypical mastitis and abortion may occur.

The causal agent is a long, fine, wavy or spiral organism, which is bent into a hook at one or both ends. It moves actively, with a rotary action, but is fragile, readily losing its vitality on exposure to drying, excessive sunlight, acids or heat.

The disease is widespread throughout the world. The best environment for the organism is warm, wet conditions with a pH value close to neutral.

Mode of spread

The source of infection is usually an infected animal which contaminates pasture, drinking water and feed by infected urine, aborted fetuses and infected uterine discharges. Transmission is mainly via infected urine.

The largest reservoir of infection is in wild animals, and of these, rodents such as rats, voles and mice are the most important. Rats can excrete the organism for at least 220 days.

In cattle, leptospires can be excreted for a period which can last from a few weeks up to 18 months, or for the animal's lifetime.

Direct transmission can occur when animals are herded together. However infection usually arises from contact with an infected environment, with infected water playing an important part in the transmission cycle. The organism may survive for months in water-saturated soil.

The organism may enter a new host through the skin, especially damaged skin, or through the mucosa of the muzzle, mouth or conjunctiva. Other routes of infection are bites from rodents; venereal spread (leptospires have been isolated from bulls' semen); animals hunting and killing infected prey; and infection of the foetus through the placenta.

Man may be infected by domestic animals, wild animals, or by contact with surface water contaminated by urine from infected animals.

Signs of Leptrospirosis

Clinical Signs

- The incubation period is usually 5-7 days. The symptoms in severe cases are those of acute septicaemia (blood poisoning) as well as fever, lack of appetite, acute anaemia (lack of blood seen in pale gums and underside of eyelids), severe jaundice and the passage of urine whose colour may range from a light-brown yellowish colour, to bright red, to almost black in some cases.

- The most severe cases usually occur in young animals, but with some serotypes, such as L. pomona , L. grippotyphosa, L. icterohaemorrhagiae and L. autumnalis adults may be also acutely affected.

- The teats are often red and inflamed. Milk flow usually ceases and there is a secretion that is red-coloured or contains blood clots. The udder is soft and limp. All four quarters of the udder are affected. There is no inflammation of the udder and the changes are due to a general vascular lesion rather than local injury to the mammary tissue.

- A skin inflammation frequently occurs in the white areas of the skin due to extreme sensitivity to light caused by liver damage.

- The animal may stamp its feet in discomfort. The muzzle may be dry, reddened and crusty and the vulva a reddish-purple colour.

- Subacute cases caused by L. pomona differ from acute cases only in degree. The fever is usually milder, but depression, lack of appetite, rapid breathing and a degree of blood in the urine still occur. Jaundice is not always present.

- Abortion may occur 3-4 weeks later, together with the characteristic drop in milk yield and the appearance of blood-stained or yellow-orange, thick milk in all four quarters, without physical change in the udder.

- In chronic cases signs are mild and may be restricted to abortion in the last third of pregnancy. Abortion "storms" may occur in groups of cattle at the same stage of pregnancy exposed at the same time to infection.

- Stillbirths and premature live births of weak calves may occur up to 3 months, and occasionally longer, after the acute stage of infection.

- Leptospirosis caused by L. hardjo occurs only in pregnant or lactating cows because the organism is restricted to growing in the pregnant uterus and the lactating mammary gland. There is sudden onset of fever, lack of appetite, and a cessation of milk yield, with a flabby udder and yellow to orange milk containing clots. The udder is non-painful. Up to 50% of animals in a herd may be affected. Abortion may occur several weeks later. Later, as natural immunity develops in adult cows, infection is restricted to heifers which show abortion only, with no mastitis.

Diagnosis

- At post-mortem examination severe jaundice, when present, is very striking. The entire carcass may appear extremely yellow, almost orange in some cases.

- There may be ulcers and haemorrhages in the abomasal mucosa, the liver may be swollen and the pattern of lobulation may be abnormally distinct.

- The kidneys may be enlarged, with the cortex a reddish-brown mottled colour.

- Urine in the bladder may be coloured red or even black.

- In chronic cases, large numbers of white spots may be seen in the kidneys.

- The identification of leptospires is difficult as they are very fragile and do not survive long in a decomposing carcass. A fluorescent antibody technique may be used, but the most commonly used method is by the demonstration of antibodies using the microscopic agglutination test by taking paired serum sample 7-10 days apart and showing a rising titre of antibodies. Serum samples will be taken by an attending veterinarian for dispatch to a laboratory. Several animals should be sampled as individual samples may be difficult to interpret. In addition milk and urine samples should also be taken for analysis.

Differential Diagnosis

- Leptospirosis should be differentiated from Babesiosis (Redwater), Anaplasmosis, Acute Haemolytic Anaemia which occurs in calves after drinking large volumes of cold water, Chronic Copper Poisoning, Rape and Kale Poisoning and in the less acute cases, differentiation from other causes of abortion.

Treatment

- This must be started early to prevent irreparable damage to liver and kidneys and to prevent the development of the carrier state.

- Streptomycin is the drug of choice in the control of infection, but one of the tetracyclines may also be effective.

- In acute infections streptomycin is given for 3 consecutive days at a rate of 25mg/kg bodyweight daily.

- A single injection of 25mg/kg dihydrostreptomycin is effective in eliminating urinary tract infections.

- No treatment is successful once a haemolytic crisis has developed.

Prevention and Control

- Vaccination with or without antibiotic therapy (dihydrostreptomycin at 25mg/kg to all cattle in the herd) offers an effective method of preventing and controlling infection in cattle herds.

- In closed herds vaccination of all members of the herd should be carried out annually while in open herds vaccination should be carried out every 6 months.

- The vaccine should be a multivalent one giving protection against those serotypes diagnosed or locally endemic. In a few animals, vaccination may fail to prevent colonization of the renal tubules and the development of a carrier state.

- In addition to vaccination steps should be taken to avoid animal contact with infected surroundings. Damp areas should be fenced and pens disinfected after use by infected animals.

- Cattle should be separated from pigs and wildlife. Rats and other rodents should be controlled.

- Replacement stock should be selected from herds which are sero-negative for leptospirosis and replacement stock should be vaccinated and treated with streptomycin.

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy ( Mad Cow Disease)

Apart from cattle BSE has been transmitted experimentally to several other species, including mice, pigs, sheep, goats, mink, monkeys and marmosets. During the British epidemic cases of BSE occurred in small numbers of captive ungulates - nyala, gemsbok, eland, oryx, kudu, Ankole cow and bison - and in five species of wild cat - puma, cheetah, ocelot, lion and tiger - either kept in, or originating from, British zoos. The ungulates were infected from the same food source as cattle and the cats, including a small number of domestic cats, were most likely infected by eating infected bovine tissue.

Only the U.K. has experienced the disease in epidemic proportions, but lower incidences have occurred in cattle in several countries in Europe, Israel , Canada , Japan , the Falkland Islands and the Sultanate of Oman . Cattle may have been infected as a result of the importation of cattle and /or ruminant-derived meat and bone meal from countries with the disease.

Cause

The precise cause of BSE is not known. It is believed to be an abnormal protein called a prion. Such agents, in addition to causing Scrapie in sheep, are also responsible for Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Kuru and Fatal Familial Insomnia in humans.

Transmission

This is via food-borne exposure to a Scrapie-like agent via contaminated meat and bone meal included in cattle rations. Transmission between cattle seems not to occur, although calves born to affected cows have a maternally associated risk. The average age when symptoms appear is 5 years, and there is no sex or breed predisposition. The incidence in herds is generally low. At the peak of the epidemic in Britain is it was an average of 2 %.

Clinical Findings

Initially these are slight and associated with the animal's behaviour. Over the following weeks and months the symptoms progress and increase arriving at a terminal state by 3 months after onset. Close observation will reveal various neurological abnormalities. These include nose licking, teeth grinding, head rubbing, nose wrinkling, sneezing or snoring. Head shyness, kicking, and frenzy may also occur. There may be an exaggerated response to unexpected visual, auditory or tactile stimuli. Long periods may be spent standing with a fixed staring expression, the head held low to the ground. As the disease progresses there is staggering and collapse accompanied by general paralysis. There is weight loss and a reduction in milk yield. Euthanasia (destruction of the animal) is advisable at this or an earlier stage.

Diagnosis

This can only be done by advanced laboratory techniques, using histopathology and electron microscopy to examine brain tissue. Differential diagnosis includes Rabies, Lead Poisoning, Brain Abscess, Hypomagnesemia, Nervous Ketosis, Trauma to the Spinal Cord and Ecephalitic Listeriosis. The lengthy course of BSE however, should help in reaching a diagnosis, as most other conditions are much shorter in their clinical manifestations.

Treatment and Control

- There is no treatment.

- Control has been effected in Britain and other European countries by banning the use of any tissue from warm blooded animals in the rations of all farm animals. Animal protein, including that derived from birds, should NEVER be fed to livestock.

Zoonotic Risk

Associated with the emergence of BSE has been a novel variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in the human population of Great Britain , in 1996. Cases have also been seen outside Britain . Infection is presumed to be the result of eating infected bovine tissue. As a result BSE affected countries have introduced the statutory removal of high-risk bovine tissue from the human food chain.

Mange

For complete datasheet please see here: Skin problems

Mange is a very itchy skin condition that comes when the skin is infected by small borrowing mites called sarcoptic mites. It may affect all warm blooded animals including humans. Humans may get it from any of the domesticated animals that have an infection.

Orf

See under Skin Problems

Orf is an infectious viral skin disease of mainly sheep and goats. It mainly affects the lips of young animals. The disease is more severe in goats than in sheep. It can also affect wild sheep and goats. Humans are occasionally infected and the disease has been reported in dogs that have scavenged on infected carcases.

It is characterised by the development of pus-filled and scabby wounds on the muzzle and lips of lambs and kids, by the appearance of similar lesions on the teats of nursing ewes and nanny goats and it can also produce lesions on the teats of cows.

Epidemics tend to occur twice yearly - the first peak is associated with the disease in sucking lambs, the later one with susceptible stock lambs. But sporadic cases can occur at any time.

The disease is commonest in lambs and kids aged 3-6 months, although lambs aged 10-12 days and adults can be severely affected. Outbreaks can occur at any time but are most common in dry conditions. Recovered animals are solidly immune for 2-3 years but they do not transfer this immunity in their colostrum to their lambs, which are therefore susceptible to infection.

In humans typical wounds occur at the site of infection, usually an abrasion infected while handling diseased sheep, or milking infected cows or by accidental means when vaccinating sheep. The lesions are very itchy and respond poorly to treatment.

Infection only occurs if there is a break in the surface of the skin or the lips. The rapid spread during dry conditions may be due to scratches on the skin caused by dry feed, allowing a ready entry of infection. Spread in a flock is very rapid and occurs by contact with other infected animals or non-living objects. Ewes nursing affected lambs often develop crops of lesions on their teats which sometime lead to mastitis. As a result lambs are unable to suckle and may suffer from starvation.

Pseudo cow pox

See under Skin Problems

Orf is an infectious viral skin disease of mainly sheep and goats. It mainly affects the lips of young animals. The disease is more severe in goats than in sheep. It can also affect wild sheep and goats. Humans are occasionally infected and the disease has been reported in dogs that have scavenged on infected carcases.

It is characterised by the development of pus-filled and scabby wounds on the muzzle and lips of lambs and kids, by the appearance of similar lesions on the teats of nursing ewes and nanny goats and it can also produce lesions on the teats of cows.

Epidemics tend to occur twice yearly - the first peak is associated with the disease in sucking lambs, the later one with susceptible stock lambs. But sporadic cases can occur at any time.

The disease is commonest in lambs and kids aged 3-6 months, although lambs aged 10-12 days and adults can be severely affected. Outbreaks can occur at any time but are most common in dry conditions. Recovered animals are solidly immune for 2-3 years but they do not transfer this immunity in their colostrum to their lambs, which are therefore susceptible to infection.

In humans typical wounds occur at the site of infection, usually an abrasion infected while handling diseased sheep, or milking infected cows or by accidental means when vaccinating sheep. The lesions are very itchy and respond poorly to treatment.

Infection only occurs if there is a break in the surface of the skin or the lips.

The rapid spread during dry conditions may be due to scratches on the skin caused by dry feed, allowing a ready entry of infection. Spread in a flock is very rapid and occurs by contact with other infected animals or non-living objects. Ewes nursing affected lambs often develop crops of lesions on their teats which sometime lead to mastitis. As a result lambs are unable to suckle and may suffer from starvation.

Q-fever

For complete description please read under Abortion and Stillbirth.

Q Fever was first identified in Queensland, Australia; hence its name. Q Fever is a disease passed to humans from sheep. People working around domestic sheep should consider getting vaccinated against this disease. The disease can be acquired from the inhalation of aerosolized barnyard dust should it contain infected dried urine, manure particles, or dried fluids from the birth of calves or lambs or through tick bites or by drinking raw milk.

Q-fever is found all over the world, in every country where it has been sought. Its main importance is its ability to infect man, and to cause abortions, metritis (inflammation of the lining of the uterus), and mastitis in infected ruminants.

Ventral view of a larval Ixodide, Dermacentor marginatus hard tick that has been cleared and mounted. This tick species is known to be a vector for Tick-borne encephalitis virus, caused by a member of the Tick-borne encephalitis virus complex, Flaviviridae, and Q fever, which is caused by the bacteria Coxiella burnetii. Coxiella burnetii is an extremely difficult organism to eliminate. It is very tough, resisting most disinfectants, heat and drying, and surviving for years in dust

At-risk animals, and man, become infected by inhaling infected fluid discharges in the air or dust loaded with dried discharges.

The disease is highly infectious. Animal handlers are particularly at risk from infection, especially at lambing or calving, from inhalation, ingestion or direct contact with birth fluids or afterbirth.

However. the main route of most human infections is by inhalation of contaminated air droplets or dust originating in infected ruminants or other animals e.g. cats.

Spread can occur up to 10 kilometres from the source of infection by wind dispersal of dried reproductive products, such as afterbirth, genital discharges, etc from infected sheep, cattle and goats, depending on wind condition.

Rabies

Local names:

Luo: Tuo swao, Rabudi, swawo / Swahili: Kichaa cha mbwa / Turkana: long'okwo, arthim, nkerep, nkwang' / Somali: ramis, nyanyo, waalan, walan / Samburu: nkuang, nkwang / Maasai: Olloitirwa LolLdien, enkeyian orki, enkeya oldian / Meru: nthu cia kuuru / Maragoli: bulalu vwa tsimbwa / Gabbra: nyanye, aidurr / Kamba: mun'gethya, nduuka ya ngiti / Kipsigis: miotap ngokto /

Common names:

hydrophobia, lyssa, rage (French), rabia (Spanish) Tollwut (German)

Introduction

| WARNING: Rabies is a notifiable disease! If you suspect an animal has Rabies, you must inform the authorities immediately. |

Rabies is is a fatal viral inflammation of the central nervous system caused by Rhabdovirus. It occurs world wide and affects all warm blooded animals including man and other domestic and wild animals except birds.

Rabies is common in both rural and urban areas. Many people are unaware of the mortal dangers associated with this terrible disease. Many people in rural areas keep dogs both as pets and for security. Because most rural people are not aware of the hazards of the disease, they have not had their dogs vaccinated. As a result lives are put at risk for the lack of simple information and a few shillings.

Furious stage of Rabies in cattle: Salivation, dropped lower jaw and squinting can be seen on this highly exited rabid cow. Whilst pressing its head onto the fence it was producing a highly abnormal bellowing sound

Mode of spread

Rabies is transmitted via the saliva of an infected animal, usually through its bite. Once clinical signs appear it is almost invariably fatal.

Rabid animals usually excrete the virus in their saliva 2 days before they show clinical signs and then throughout the course of the disease which is normally less than 10 days. On rare occasions dogs in Africa have been known to survive Rabies and to excrete the virus in their saliva for months.

Transmission usually occurs when infected saliva is deposited in a bite wound. Less common routes of transmission include inhalation of infected droplets in bat infested caves and by the ingestion of an infected carrier.

The rabies virus spreads when it is deposited in a bite wound and penetrates muscle cells where it either multiplies or becomes confined as a subviral particle. Within a few hours newly formed viral particles enter the peripheral nervous system and travel along the nerve trunks to the spinal cord and brain. From the brain the virus travels along peripheral nerves to the salivary glands.

In Kenya the dog is the main transmitter of Rabies though cats and wild animals, such as jackals, can also play a part in transmission. Ruminants such as cattle, sheep and goats play little part in direct transmission but their role as indirest transmitters can be important. The disease is of serious concern as the majority of dogs in the country are unvaccinated.

The incubation period is both prolonged and variable. Bites close to the head result in symptoms appearing sooner than in an animal bitten, for example, on a lower hind limb. Sequestration of the virus in the area of the bite is believed to explain the occasional very long incubation periods recorded. Bites in areas with a rich blood supply are especially dangerous. In most clinical cases of Rabies the incubation period is of the order of 3 to 12 weeks, with occasional cases of periods of up to a year.

Signs of Rabies

The course of the clinical disease ranges from 2 to 10 days.

There are three clinical phases: pre-symptomatic, excitative and paralytic.

1. Before symptoms occur (pre-symptomatic phase) there is a change in behaviour; friendly dogs become aggressive, fierce dogs become friendly. Affected cattle stray away from the herd. In dogs this phase may last for 2-3 days; in cattle a few hours.

2. The excitative phase is refered to as "Furious" Rabies. In the excitative phase:

- Animals appear to be hypersensitive, restless, and agressive and may bite or attack without warning

- Voice changes occur. Depending on the species of the infected animal, the voice changes may include howling, roaring and bleating. Infected people may bark like dogs

- Dogs often have a peculiar staring expression and often drool saliva

- The conjunctiva often is red and inflamed

- They may attack any moving object and break their teeth and eat stones and sticks

- Cattle may stare intently at people before charging them. They may break their way through fences.

- Donkeys may mutilate themselves biting and chewing their bodies to such an extent they occasionally even disembowel themselves

- Cats become very aggressive, attacking without provocation.

3. The paralytic phase is refered to as "Dumb" Rabies. In the paralytic phase:

- Cattle may walk unsteadily and strain unproductively as though trying to pass dung, due to decreased sensation of the hindquarters

- They bellow hoarsely, continuously, sometimes for hours on end

- They drool saliva

- They are unable to eat or drink

- Dogs often have paralysis of the lower jaw, with a dry, darkened tongue

- Finally the animal becomes progressively paralysed,cannot eat or drink and dies.

The period from the onset of symptoms to death is generally short, usually 3 to 4 days. Occasionally a rabid animal may show no obvious clinical symptoms and may die after a short undramatic illness.

Diagnosis of Rabies

- Any animal behaving strangely should be suspected of having Rabies. The absence of a bite wound is immaterial as bites, if they had been present, will have have healed long before the advent of symptoms.

- Animals acting oddly should not be approached closely. Do NOT put hands into any animal?s mouth searching for suspected non-existent foreign bodies. If saliva gets onto the hands they should be immediately washed vigorously with soap and disinfectant.

- Medical advice should be sought if there is ANY suspicion that an animal might have Rabies and a veterinary surgeon sought to examine the affected animal.

- Animals suspected of having Rabies should be isolated, confined and otherwise kept enclosed and out of touch of people and other animals, until such time as the animal is either dead or alive at the end of 10 days. If the animal is still alive after10 days one can confidently assume that it did not have Rabies.

- In the case of dogs and cats the head will be examined at Kabete Central Veterinary Laboratories, brain tissue being tested using the Direct Immunofluorescent Test. The result should be available after a day. With cattle the size of the head and the difficulties of transporting such a cumbersome mass to Kabete laboratory makes this a matter harder to resolve.

- Do NOT attempt to remove the head yourself. This is a job for a trained veterinarian only!

- A laboratory diagnosis is important but in the absence of this if the symptoms suggest Rabies it is better to assume that that is what it is, rather than to do nothing and wait for the next case.

Prevention - Treatment - Control

There is no treatment for rabies and it is not advisable to try to treat an animal infected with rabies because of the dangers in handling such an animal.

Recommended prevention and control

- All owned dogs must be vaccinated. It is advisable to conduct a mandatory vaccination of all domestic dogs. Since rabies is regarded as notifiable disease, the campaign should be enforced by relevant veterinary act and a breach of the act should be punished by the law.

- Regular baiting of stray dogs in the urban and rural areas: After every vaccination campaign against rabies, all stray dogs and other dogs that have not been vaccinated should be baited in accordance with an enforcing act.

- Joint collaboration: Effective control of rabies requires a joint collaboration between various stake holders such as: veterinary department, public health, provincial administration and ministry of education and the public.

- Avoid contact with any dogs and cats which do not have owners

- Keep stray dogs and jackals away from livestock

Warning!!!

- Remember always that there is NO treatment for Rabies! Do NOT try to treat an animal with Rabies! It is going to die and so might you, if you get bitten.

- Anyone bitten by a rabid animal or who has had close contact with one, whether dog, cow, donkey, sheep or cat MUST receive a course of post-exposure anti-rabies vaccinations. As soon as possible.

- The cost of anti rabies vaccine for human immunization is expensive. In Kenya the cheapest anti rabies vaccination course for a human would cost about Kshs.10,000 in a public hospital or more in a private hospital. Therefore it is cheaper to vaccinate a dog at a cost of Kshs.50. This should be repeated yearly. This would protect your dog from getting or transmitting Rabies.

- Remember also that the Kenyan law requires that all dogs must be vaccinated against Rabies

- Rabies is a notifiable disease and therefore any suspected case of rabies should be

Rift Valley Fever

For complete description please see: Flies and Mosquito borne diseases.

Rift Valley Fever (RVF) is a mosquito-borne viral disease affecting domestic ruminants (cattle, sheep, goats, camels, domestic buffaloes) and humans. It occurs mainly in East and Southern Africa and in year 2000 in Saudi Arabia and Yemen. During epidemics the occurrence of numerous abortions, deaths in young animals and influenza like diseases in humans tends to be characteristic. During recent epidemics in Kenya several deaths of humans were reported.

Formerly, apart from abortion, most cases in adult animals were subacute, but in recent times a haemorrhagic form of the disease has emerged with rapid death in mature animals, including cattle.

There is a remarkable age-related innate resistance to RVF virus; mortality rate in lambs less than 1 week old exceeds 90% whereas the rate in lambs over 1 week drops to 20%.

The virus is widely distributed in Africa, but major epidemic episodes in animals and humans are relatively rare, occurring in 5 to 20 year cycles. Between epidemics, the virus survives in mosquito eggs laid on vegetation in dambos-which are shallow depressions in forest edges. Only when these are flooded do the eggs hatch. This only occurs when the water table rises following prolonged heavy rain. The eggs then hatch and a new population of infected mosquitoes emerges.

Heavy rains and flooding cause mosquito eggs to hatch and Rift valley fever to become epidemic.

Vaccination of all domestic animals at the onset of heavy rains is a good precaution which will also protect humans from catching this serious disease.

Ringworm

For complete description please read under Skin Problems

Ringworm is a fungal skin infection - not a worm at all. Children are often observed with ringworm infestation. They can get ringworm infections from any domestic animal or from other children. Ringworm in children can be cured by using special medicated soaps. In animals use of iodine or chlorhexidine (Savlon) can be effective cures along with cleaning out their pens and living areas.

Sings of Ringworm

- Animals and humans develop symptoms of ringworm 7 - 28 days after infection.

- Animals have a circular scab on the skin about 3 cm across. Scabs usually appear first around the nose, above and around the eyes, on the ears or under the tail. The skin under the dry scab is wet. Scabs soon join together and become thicker.

- In children ringworms are often seen on the scalp, arms and any part of the body not often exposed to sunlight

- After several days the scabs fall off. The skin underneath becomes dry with a heavy, gray-white crust raised above the skin.

- Animals do not scratch when they have ringworm. But they sometimes scratch if bacteria infect the scabs.

- The scabs fall off after a few weeks and leave patches with no hair.

Animals slowly recover even without treatment. The hair grows back in about three months

Salmonellosis

Salmonella causes serious diarrhea and if untreated - causes death in humans and animals - read under Salmonellosis

Taeniasis or Tape worms

See also Worms

Taenia saginata

This is a tapeworm of humans, in which it can cause abdominal discomfort. It is a very long tapeworm, growing up to 15 metres long. It can cause loss of weight and general weakness in humans

Adult Taenia saginata tapeworm. Humans become infected by eating raw or undercooked infected meat. In the human intestine the cysts (larval stage) develop over 2 months into adult tapeworms which can survive for years. They attach to and feed from the small intestine.

Tetanus

Introduction

Tetanus is a poisoning, caused by the neurotoxin of the spore-forming bacterial organism, Clostridium tetani, characterized by muscular spasms.

The disease occurs worldwide, but is more common on well-manured land, in closely settled areas under intensive cultivation, or associated with surgical procedures. Cases are usually sporadic, although occasionally outbreaks involving several animals may occur, as in lambs or colts as a result of infection through operation wounds or via the naval cord.

Almost all mammals are susceptible to Tetanus, including humans, who are very susceptible. Among mammals horses are the most susceptible, followed by sheep and goats. Cattle are fairly resistant, as are dogs. Cats seem to the most resistant of all domestic animals.

Mode of spread:

Clostridium tetani is an anaerobe - it lives without oxygen. It is found in soil and in intestinal tracts and in faeces. The spores may persist in the ground for many years, and are very resistant to heat and to standard disinfectants. In most cases they are introduced into the tissues through wounds, particularly deep puncture wounds, which provide a suitable anaerobic environment. Horses' hooves are particularly susceptible. Cows after calving may also contract tetanus. In lambs, however, it often follows docking or castration.

Sometimes the point of entry cannot be found because the wound itself may be minor or have healed.

The spores of C. tetani are unable to grow in normal tissue or even in wounds if the tissue remains at the oxidation-reduction potential of the circulating blood that is surface wounds. Suitable conditions for multiplication occur when a small amount of soil or a foreign object causes tissue damage and cell death such as deep puncture wounds. When this happens the bacteria remain localised in the destroyed tissue at the original site of infection and multiply.

Sometimes the spores may lie dormant in the tissues for some time and only produce clinical illness when tissue conditions involving a drop in the oxygen level favours their proliferation.

As the bacterial cells themselves disintegrate the potent neurotoxin is released, being absorbed by the motor nerves in the area and passed up the nerve tracts to the spinal cord. The toxin causes spasmodic, tonic contractions of muscles by interfering with the release of neurotransmitters from the nerve endings. Even minor stimulation of the affected animal may trigger the characteristic muscular spasms, which may be so severe as to cause bone fractures. Respiratory failure may occur due to spasm of the larynx, diaphragm and muscles of the chest.

Symptoms

The incubation period varies from one to several weeks, but usually averages 10 - 14 days.

- The initial signs are often no more than a little stiffness, anxiety and an exaggerated reaction to handling or to noise. Soon, however, after about a day or so, the stiffness becomes more general. The muscles of mastication, the neck, the hind legs and the area of the infected wound are most affected. Spasms and greater reaction to stimuli become evident.

- Cattle may show signs of bloat.

- Animals may be constipated and urine may be retained because of difficulty in attaining the normal posture for urination.

- The reflexes increase in intensity, and the affected animal is easily excited into more violent, general spasms by sudden movement or noise. The third eyelid, is often partially prolapsed across the surface of the eye, producing a snapping noise as it does so. The ears are usually stiff and erect and immobile. Any movements are slow and accomplished with great difficulty. The legs cannot be flexed. The jaw cannot be opened due to spasm of the muscle of mastication ? lock jaw. The nostrils are dilated and the face has a peculiar staring, anxious expression. The tail is rigid and often held sideways. The affected muscles feel hard, tense, and board-like, sometimes showing twitchings and tremblings.

- Respiration becomes more and more difficult as the muscles of respiration are affected. Finally the animal falls to the ground with the head often bent backwards. The affected animal remains fully conscious throughout.

- Death usually occurs from 8 - 10 days after the appearance of the first symptoms. Mortality averages about 80% and death is from suffocation and respiratory arrest.

Diagnosis

This is usually made from the characteristic clinical signs and history of a recent wound. It may be possible to demonstrate the organisms in smears taken from a wound or by culture, but this is rarely done.

Strychnine poisoning may be confused with Tetanus, but in poisoning the onset of symptoms is much more rapid, the muscular cramps are intermittent and not constant and death occurs in a much shorter period of time.

Treatment

In humans is normally standard practice to administer tetanus vaccine immediately as part of treatment of any deep puncture wounds. Please ask your doctor for advice.

In animals proper treatment of all wounds is of primary importance. The persistence of pus, dead tissue, dirt or foreign bodies within the wound must be avoided and the proliferation of bacteria avoided. Careful drainage must be provided to prevent the accumulation of blood serum and excretions. Foreign bodies must be removed and the wound thoroughly opened to ensure careful cleaning. After any surgical procedure, such as docking or castration, animals must be turned out onto clean ground, preferably grass pastures. Remember that only oxidizing disinfectants, such as iodine or chlorine dependably kill the spores.

If symptoms have set in, place the animal in a quiet, comfortable place and do not disturb it in any way. It should receive soft, easily digestible food and, when eating becomes more difficult, gruels or milk. Plenty of fresh water should be placed within easy reach, but the administration of medicine by mouth is not advised.

Any wounds should be drained and cleaned to prevent further production of toxin, and antibiotic in the form of large doses of penicillin administered.

Tetanus anti-toxin (if available) may be administered but is of little use once symptoms have appeared. Valuable animals may be given tranquilizer or sedative drugs, such as Acetylpromazine or Chlorpromazine to act as muscle relaxants.

The outlook in any case of Tetanus is always poor, but with careful nursing and aggressive use of antibiotics and with particular attention to the cleansing of wounds, some animals may recover. But recovery is always slow and protracted and may take several weeks.

Control and Prevention

All surgical interventions such as docking lambs' tails, castrations, sheep shearing etc, should be carried in clean surroundings, paying especial care to the disinfection of skin and of any instruments used. Temporary pens for holding animals are preferable to permanent ones which are more likely to be contaminated and dirty.

Tetanus vaccine can be used to confer immunity in situations where animals may be at risk. One injection gives immunity in 10-14 days lasting for a year and revaccination in 12 months gives solid immunity for life. In areas where the disease is very common all animals should be vaccinated annually as a routine measure.

Prevention of tetanus in new-born lambs is best effected by vaccination of the ewe in the last 2-3 weeks of pregnancy, preferably by using a combined clostridial vaccine which will also confer immunity against other diseases such as Lamb Dysentery, and Pulpy Kidney Disease.

Toxoplasmosis

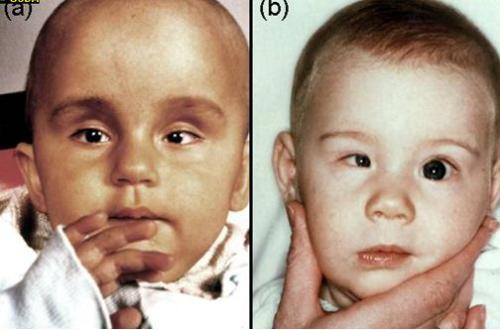

|

| Signs of Toxoplasmosis in children. (a) bulging forehead, (b) uneven size of eyes |

|

© USDA

|

|

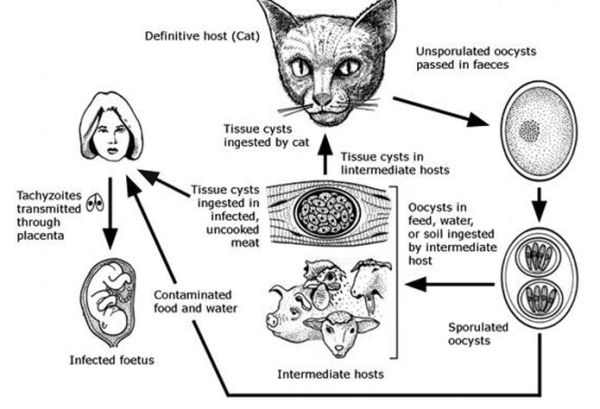

| Toxoplasma gondii life cycle - the reservoir of the parasite are infected cats |

|

© USDA

|

Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii is an important zoonotic agent. In some parts of the world up to 60% of the human population is infected during their lifespan. After infection, the vast majority of infected people become immune against Toxoplasma and never develop any signs of disease. But Toxoplasmosis is of concern to non-immune pregnant women and to people who are immuno-compromised (e.g. those infected with HIV). In non-immune pregnant women Toxoplasma can infect the fetus and cause severe congenital malformation of the brain and eyes.

Infection of humans occurs after ingestion of undercooked meat and from close contact with cats and cat litter (accidental ingestion of microscopic Toxoplasma oocysts present in cat faeces).

Definition

Toxoplasmosis is caused by a microscopic protozoal parasite, called Toxoplasma gondii, which infects humans and other warm-blooded animals, including birds, and occurs worldwide.

Infection in humans is very common, but clinical Toxoplasmosis in humans is very rare. It is also a cause of abortion and neonatal mortality in sheep.

Infection cycle

Toxoplasma is a specific parasite commonly found in cats, which are the only main host. There is a wide range of intermediate hosts, including humans, livestock, mice and other rodents and wild birds.

Cats become infected by eating raw meat (e.g. from catching and eating infected mice) Infected cats are healthy but shed Toxoplasma eggs (called oocysts) in their feces. Huge numbers of eggs may be excreted into the environment and can contaminate concentrate feed or hay for livestock. Toxoplasma eggs remain infective in the environment for long periods, exceeding a year. When eggs are ingested by a non-immune pregnant woman or by non-immune pregnant livestock the Toxoplasma invade the brain of the fetus and/or the placenta. Women or female livestock infected during childhood remain healthy and become immune for life. A later re-infection with Toxoplasma in pregnant immune females does not affect the fetus, which is now fully protected by the immune mother.

Clinical Signs

The only clinical signs seen with any regularity in livestock are abortions and neonatal mortality in sheep and also in goats. In immuno-competent humans the only visible sign of Toxoplasma infection is the birth of a child with severe congenital defects (brain and eyes). - In immuno-compromised humans toxoplasmosis can cause infection of the brain.

Prevention

There is no treatment that can protect the fetus. - Immuno-compromised humans (e.g. HIV) suffering from Toxoplasma can be treated with drugs such as sulphadiazine and pyrimethamine.

The most efficient prophylaxis is to ensure exposure to cats for children, lambs, kids early in life, such that they do acquire immunity long before they can become pregnant. There is also a Toxoplasma vaccine (Toxovax) for use in sheep, which is currently (2013) not available in Kenya.

Cats should not be allowed to mingle with farm animals and contamination of the food of farm animals with cat faeces must be prevented. Farm cats should be neutered to prevent straying and contracting and spreading infection. Cats should be kept healthy. Sick and immunosupressed cats may have a recurrence of infection.

To prevent infection people handling meat should wash their hands thoroughly with soap and water after contact. This also applies to cutting boards, sink tops, knives and other materials. T. gondii is killed by exposure to extreme cold or heat. Tissue cysts in meat are killed by heating the meat throughout to 67 C or by cooling to -13 C. The meat of any animal should be cooked to 67 C before consumption. Tasting meat while cooking should be avoided. Water should be boiled or filtered.

Pregnant women must have their immune status tested. If found not to be immune against Toxoplamsa they must strictly avoid contact with cats, cat litter, soil and raw meat. Pregnant women should also not assist at lambing time.

Pet cats should only be fed dry, canned or cooked food. The cat litter box should be emptied daily, preferably not by a pregnant woman. Gloves should be worn when gardening. Vegetables should be thoroughly washed before eating as they may have been contaminated with cat faeces. There is no human toxoplasma vaccine.

Treatment

This is rarely applicable in animals. In humans drugs such as sulphadiazine and pyrimethamine are widely used, especially in the acute stage. Clindamycin is the treatment of choice in dogs and cats.

Tuberculosis

For complete description please see under Respiratory Diseases

Tuberculosis is a bacterial infection that affects mainly cattle and human beings, as well as other domestic animals. Mycobacterium bovis is the usual cause of tuberculosis in cattle, while M.avium causes the disease in poultry and M. tuberculosis is responsible for the majority of cases in man. It occurs worldwide but prevalence is dependant on the type of husbandry and the efficacy of control measures. Its prevalence is low in cattle kept extensively and not housed at night.

| WARNING: Consumption of raw milk by humans should be discouraged. People get tuberculosis from animals. Never drink unboiled milk. |

Humans are more susceptible to tuberculosis if the immune system has other challenges such as HIV/AIDS. It is therefore often encountered as secondary infection to this disease.

Review Process

1. William Ayako, KARI Naivasha. Aug - Dec 2009

2. Hugh Cran , Practicing Veterinarian Nakuru. Sept. 2011

3. Review workshop team. Nov 2 - 5, 2010

- For Infonet: Anne, Dr Hugh Cran

- For KARI: Dr Mario Younan KARI/KASAL, William Ayako - Animal scientist, KARI Naivasha

- For DVS: Dr Josphat Muema - Dvo Isiolo, Dr Charity Nguyo - Kabete Extension Division, Mr Patrick Muthui - Senior Livestock Health Assistant Isiolo, Ms Emmah Njeri Njoroge - Senior Livestock Health Assistant Machakos

- Pastoralists: Dr Ezra Saitoti Kotonto - Private practitioner, Abdi Gollo H.O.D. Segera Ranch

- Farmers: Benson Chege Kuria and Francis Maina Gilgil and John Mutisya Machakos

- Language and format: Carol Gachiengo

CORONA

Information Source Links

- Barber, J., Wood, D.J. (1976) Livestock management for East Africa: Edwar Arnold (Publishers) Ltd 25 Hill Street London WIX 8LL

- Blood, D.C., Radostits, O.M. and Henderson, J.A. (1983) Veterinary Medicine - A textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Goats and Horses. Sixth Edition - Bailliere Tindall London. ISBN: 0702012866

- Blood, Radostits and Henderson: Veterinary Medicine A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses 6th Edition ELSB & Bailliere Tindall 1983 ISBN 0-7020-0988- 1

- Blowey, R.W. (1986). A Veterinary book for dairy farmers: Farming press limited Wharfedale road, Ipswich, Suffolk IPI 4LG

- CABI 2007 : Animal Health and Production Compendium edition (2007)

- David Buxton Toxoplasmosis in Sheep and other Farm Animals Volume 11 No 1 January 1989

- Force, B. (1999). Where there is no Vet. CTA, Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 978-0333-58899-4.

- Hall, H.T.B. (1985). Diseases and parasites of Livestock in the tropics. Second Edition. Longman Group UK. ISBN 0582775140

- Henning MW (1956): Animal Diseases in South Africa, 3rd Edition. Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute, Central News Agency Ltd., Pretoria, South Africa

- Hunter, A. (1996). Animal health: General principles. Volume 1 (Tropical Agriculturalist) - Macmillan Education Press. ISBN: 0333612027

- Hunter, A. (1996). Animal health: Specific Diseases. Volume 2 (Tropical Agriculturalist) - Macmillan Education Press. ISBN:0-333-57360-9

- ITDG and IIRR (1996). Ethnoveterinary medicine in Kenya: A field manual of traditional animal health care practices. Intermediate Technology Development Group and International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Nairobi, Kenya. ISBN 9966-9606-2-7.

- In Practice Journal of Veterinary Postgraduate Clinical Study

- Khan CM and Line S (2005): The Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th Edition, Merck & Co Inc Whitehouse Station NJ USA

- Mackenzie & Simpson 1967: The African Veterinary Handbook 4th Edition, Pitman

- Mackenzie & Simpson 1967: The African Veterinary Handbook 4th Edition, Pitman

- Martin WB 1983 Editor: Diseases of Sheep by Blackwell Scientific Publications ISBN 0-632-01008-8

- Mearns Rebecca January 2007: Abortion in Sheep: Investigation and Principal Pathogens Volume 29 No 1

- Merck Veterinary Manual 9th Edition

- Michael Lappin Feline Toxoplasmosis: Current Clinical and Zoonotic Issues Volume 21 No 10 November/December 1999

- Mike Taylor November/December 2000: Protozoal Disease in Cattle and Sheep Volume 22 ISBN NO 0263/841 X

- Mugera GM (editor) (1979): Diseases of Cattle in Tropical Africa. Kenya Literature Bureau PO Box 30022 Nairobi

- Sewell and Brocklesby (1990): Handbook on Animal Diseases in the Tropics 4th Edition Bailliere Tindall ISBN 0-7020- 1502-4

- The Organic Farmer magazine No. 50 July 2009

- The Organic Farmer magazine No. 51 August 2009