In this section listed are the diseases that are to a large extent management and environment related, such as diarrhea, bloat, FMD, foot problems and mastitis. It contains also information of the disease Rinderpest, which has now been declared extinct in East Africa, so that in case it resurfaces, there will be at least reference material.

Also Nairobi sheep disease, PPR and Plant and other Poisoning are included here.

Introduction

In this section is listed the diseases that are to a large extent management and environment related, such as diarrhea, bloat, FMD, foot problems and mastitis, but also mention signs to look for the disease Rinderpest, which has now been declared extinct in East Africa, so that in case it resurfaces, there will be at least reference material.

Also Nairobi sheep disease, PPR and Plant and other Poisoning are included here.

Bloat

|

Local names: Luo: ich-kuot / Embu: nunvita / Gabbra: furfur / Gikuyu: huhita / Kamba: kwimbanywa / Kipsigis: kowiren / Maasai: Embo'ngit, Ediis, empomgit / Maragoli: kuhaata, myika munda/ Meru: mpwna / Samburu: mberini / Somali: bakhakh, dunbudhyo, balao, baalallo, dhibir, dibiyio / Turkana: lotebwo, akitebukin, akiurur / Pokot: lesana /

Other name: Ruminal Tympany

|

Introduction

With the onset of long rains, livestock keepers, especially goat, sheep and cattle keepers should become aware of the dangers of bloat to their livestock. Bloat occurs when there is an abrupt nutritional change in the diet and especially when ruminants feed on lush green pastures. It simply means animals have too much gas in their stomach.

|

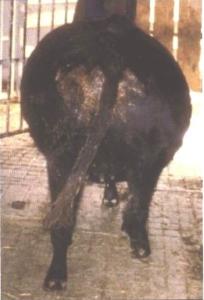

| Cow with bloat |

|

© W. Ayako, KARI Naivasha

|

|

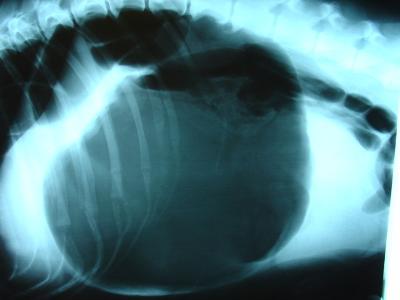

| X-ray - dog with bloat |

|

© Joel Mills, Wikipedia

|

How animals get bloat

The rumen of cattle, sheep and goats is like a large container in which a mixture of partly digested feed and liquid is continuously fermenting, producing large quantities of gas. For example, an average cow can produce over a thousand litres of gas in a day. Some of the gas is removed by absorption into the blood stream but most of it is removed by belching during "cudding". If the gas cannot escape, the rumen literally "blows up" and the animal gets bloat. It can happen when:

- Animals eat too many legumes or too much fresh, lush grass (e.g. olenge grass (Luo))

- Animal eats too much grain (e.g. finger millet, Acacia pods)

- Animal eats cassava leaves or peels

- Something blocks the passage of food in the stomach or gullet

Types of bloat

There are two types of bloat: Frothy Bloat and Free Gas Bloat.

Animals get Frothy Bloat when the rumen becomes full of froth (foam). Several animals in the herd may get this type of bloat at the same time when they graze on wet, green pasture mixed with legumes in the field. Foaming substances are found in certain plants such as legumes of which lucerne, clover and young green cereal crops are examples.

Frothy Bloat is due to the production of a stable foam, which traps the normal gases of fermentation in the rumen. Pressure increases because belching cannot occur. Initially the distension of the rumen stimulates rumen movements, which makes the frothiness even worse. Later on because of the distension there is loss of muscle tone and loss of the rumen's ability to move spontaneously, compounding the situation.

Saliva has antifoaming properties. More saliva is produced when food is eaten slowly than when it is eaten quickly. Succulent forages are eaten more rapidly and digested more quickly and as a result less anti-foaming saliva is produced. Grazing on immature, lush, succulent, rapidly growing pastures with a high concentration of soluble proteins is most conducive to bloat, as is the stage of growth of the plant, not its degree of wetness.

Causes of Frothy Bloat

- The primary cause of frothy bloat appears to be a change in the composition of certain pasture plants, the change being one that facilitates the development of a stable foam that in turn prevents belching

- Frothy Bloat normally happens at the start of wet season when the diet of grazing animals abruptly changes from dry feeds to wet lush pastures that contains some legumes.

- Animals also get Frothy Bloat when they feed on ripe fruits or other feeds that ferment easily.

- Some poisonous plants can cause sudden and severe bloat.

- A sudden change in the type of food can also cause Frothy Bloat.

- Frothy bloat can also occur in feedlots with insufficient roughage, or food too finely ground. This leads to a shortage of rumen-stimulating roughage, and prevents the rumen's ability to move spontaneously and hinders belching and release of gas.

Free Gas Bloat is usually due to physical obstruction of the oesophagus, often by a foreign body such as a potato, avocado, apple etc. Grain overload leading to stopping of of normal rhythmic contractions of the rumen wall can also cause this type of bloat as can unusual posture, particularly lying down, as may occur in a cow affected by milk fever. This type of bloat normally only affects one or two animals in the herd at the same time, not several as in the case of Frothy Bloat. As the name suggests, in this type of bloat the gas lies above the food in the rumen and is not mixed with it, as it is in Frothy Bloat.

Signs of Bloat

- The left side of the abdomen behind the ribs becomes very distended and very tense, like a drum. Later the right side also becomes distended

- The animal stops eating

- The animal may grunt and have difficulty in breathing

- There may be mouth breathing

- The animal may stamp its feet on the ground

- Sometimes green froth comes out of the mouth and nose

- There may be extension of the tongue from the mouth

- Diarrhoea is common in cases of Frothy Bloat

- Animals may collapse and die after only an hour or so

- There is often frequent urination

Prevention - Control - Treatment

Prevention of bloat

1. Feed the animals with dry grass or hay to fill them up before you turn them out onto new wet lush pasture. For this to be effective the hay or dry grass should form at least one third of the diet.

2. Do not water the animals just before you put them on to wet pasture

3. Do not graze the animals on wet green pasture early in the morning. Wait until the pasture has been dried up by the heat of the morning sun

4. You should gradually increase the grazing hours of the animals on wet green pasture over the first week. Do not put the animals out all day and leave them there.

5. Avoid abrupt changes in the diet of animals and always give newly introduced feeds in small quantities.

6. If possible try to strip graze animals to reduce intake and to maintain grass dominance in the stretch of grass. The pasture ideally should have at least 50% grass.

7. During the risk period the continual administration of anti-foaming agents such as Stop Bloat should be considered.

8. Watch animals closely at all times during the risk period.

9. Keep anti-foaming agents close at hand during the risk period.

10. In feedlot or zero grazing situations rations must contain 10-15% chopped roughage mixed into the complete diet. This should be a cereal, grain straw, grass hay or equivalent. Grains should be rolled or cracked, not finely ground.

Treatment of bloat

Depending on the type of bloat, several methods of treatment can be applied:

- Do not feed the animal for a few hours and make the animal move around (remember it can die within 1 hour if the bloat is severe)

- For less severe cases of frothy bloat, give 500 ml to large animals and 100ml to small animals of any edible vegetable oil, solid cooking oil, butter oil, ghee or milk orally (by mouth). Non-toxic mineral oils can also be used effectively.

- Severe bloat is an emergency and rapid action is required to save the animal's life. In life-threatening cases where the animal can not breathe, an emergency rumenotomy may be necessary. Puncture carefully the skin and the rumen of the animal on the left flunk to let the gas out. Use a knife or any sharp thing but the best instrument to use is the trochar and cannula. The hole should be made at a hands' width behind the last rib and a hand away from the edge of the backbone. Push hard because the skin is very tough. Gas and froth will come out when you make the hole. It helps to put a tube or cannula through the hole to keep the hole open. There will be an explosive release of gas and rumen contents. Remember that in severe cases if this is not done the animal will die. SO DO IT .

- Pour some vegetable oil into the rumen through the hole to help stop further gas or froth formation. Complications are rare. Call a veterinarian to attend to a punctured abdomen or a difficult case of bloat.

- Another aid is to tie a stick in the mouth to stimulate the flow of saliva, which is alkaline and helps to denature the foam.

- Forceful walking may help to coalesce the foam into larger bubbles and stimulate belching.

- Give bloat medicine such as the following: Stop Bloat, Bloat Guard or Birp once daily for 3 days

- In cases of Free Gas Bloat due to a foreign body lodged in the oesophagus, it may have to be dislodged by using a probang or stomach tube, for which the services of a veterinarian will be required.

Common traditional practice

Some of the following practices may have some merit in case of emergencies where no vegetable oil is available:

- Gabbra: Mix 4 teaspoons of laundry detergent with 1 litre of milk. Drench 1 litre for an adult cow (0.5 litre for sheep and goats)

- Turkana: Mix 500 g Magadi soda with 1 litre of water. Stir well and drench adult cattle with the mixture. For calves, goats and sheep use 0.5 litre. For large camels give 2 litres.

- Luo: Mix 0.5 litre of paraffin oil with a handful of olulusia (Vernonia amygdalina) leaves and 2 spoons of salt. Drench with half this amount.

- Kamba: Mix a handful of wood ash with 1 soda bottle (300 ml) of water. Sieve and drench adult cattle with this amount. Use half the amount for calves, sheep and goats.

(Source: ITDG and IIRR 1996)

Enterotoxaemia

Introduction

Enterotoxaemia is caused by the bacterium Clostridium perfringens, an organism which is widely distributed in the soil and in the gastrointestinal tract of animals. It is characterized by the ability to produce potent exotoxins (poisons). The bacteria are also capable of forming spores which survive for long periods in soil. Five types have been identified, the most important of which are A, B, C and D.

The spores of Clostridium perfringens Types B, C and D are found in soil and faeces of normal animals in areas where disease is prevalent as well as in the intestinal contents of infected sheep. Their presence in the intestinal tract of normal animals is important because they are able to form the focus for a fatal infection as and when conditions alter to allow their rapid multiplication.

The organism multiplies extremely rapidly in the presence of high levels of carbohydrate when oxygen tension is low. Thus, in cases of Lamb Dysentery, disease is most prevalent in lambs which ingest large quantities of milk. So heavily-milking breeds are more susceptible than lighter-milking breeds. A similar situation exists with Pulpy Kidney Disease, when a change of diet from one consisting mostly of roughage to one predominating in grain, allows starch granules to move into the duodenum, where they form an ideal medium for the multiplication of the bacteria, which produce toxin (poison).

Type A

This occurs as part of the normal, intestinal microflora of animals, and produces the lethal and necrotizing alpha toxin, causing necrotic enteritis in poultry and dogs, colitis in horses and diarrhoea in pigs.

The disease is characterized by a necrotic enteritis in which there is massive destruction of the villae (small finger-like projections in the gut which increase surface area and thereby improve food absorbtion), and coagulation necrosis (death of tissue) of the small intestine. In dogs there may be a haemorrhagic (bloody)diarrhoea.

Types B and C (Dysentery)

These types cause severe enteritis (stomach infection), dysentery (very severe diarrhea, often with blood and mucous), toxaemia (blood poisoning) and high mortality in young lambs, calves, pigs and foals.

Types B and C both produce the highly necrotizing and lethal beta toxin, which is responsible for severe intestinal damage. Adult cattle, sheep and goats can be affected by enterotoxaemia caused by Type C.

Lamb Dysentery occurs in lambs up to three weeks of age and is caused by Type B. Calf Enterotoxaemia is caused by Types B and C in well fed calves up to one month of age. Pig Enterotoxaemia occurs during the first few days of life and is caused by Type C. Foal Enterotoxaemia occurs during the first week of life and is caused by Type B. Struck is caused by Type C in adult sheep, while Goat Enterotoxaemia in adult goats is also caused by Type C.

Signs of Enteroxamia (Dysentery)

Lamb dysentery is an acute disease of lambs less than three weeks old. Many die before symptoms are seen. Others stop suckling, become listless, have a foetid (foul smelling), blood-tinged diarrhoea and die within a few days.

In calves there is acute diarrhoea, dysentery, abdominal pain and convulsions. Death may occur within a few hours, but less severe cases may survive for a few days and occasionally recovery may occur.

Most affected piglets die within a few hours with diarrhoea and dysentery. In foals there is acute dysentery, toxaemia and rapid death. Struck is characterized by sudden death in adult sheep.

Diagnosis

Post mortem findings reveal in all cases a haemorrhagic (bloody) enteritis (Stomach infection) with ulceration of the mucosa. Smears of the gut contents reveal large numbers of gram positive rod-shaped bacteria, while filtrates will reveal and identify the toxin.

Control and Prevention

Because the disease is so severe, treatment is usually ineffective. Oral administration of antibiotics may be helpful in some cases.

The disease in lambs is best controlled by vaccination of the pregnant dam during the last third of pregnancy, initially 2 vaccinations one month apart and annually thereafter.

When outbreaks occur in newborn animals from unvaccinated dams, antiserum, if available, should be administered immediately after birth.

Type D (Pulpy Kidney Disease)

This type causes Pulpy Kidney Disease of sheep.

It occurs world wide and may occur in animals of any age, but occurs most commonly in 3 - 12 week old lambs and in fattening lambs 6 - 12 months old. Single lambs are more susceptible than twins. Morbidity seldom exceeds 10% but mortality is usually 100%.

It is caused by the rapid multiplication of the organism in the small intestine and the subsequent absorption of the epsilon toxin, which is produced by the organism in the form of a non-toxic prototoxin and is converted to a lethal toxin by the action of trypsin.

The toxin increases the permeability (ability to pass through) of the intestinal mucosa to this and other toxins, thus facilitating its own absorption. The first effect of the toxin is to cause a profuse (heavy), mucoid (slimy) diarrhoea and then to produce a stimulation and then a depression of the central nervous system.

Lambs on lush grazing or being fed grain in feedlots, are particularly at risk.

Signs of Pulpy Kidney disease

Pulpy Kidney Disease is peracute (very severe) and of short duration, with most cases being found dead. Those that are observed before death show hyperaesthesia (excessive reaction to being touched and other stimuli), staggering progressing to lying down, with its head twisted back over the back, intermittent convulsions, occasional diarrhoea and death. Affected animals do not recover.

Diagnosis

At post mortem

- the animal is usually in good condition

- there is an excess of straw-coloured fluid around the heart,

- haemorrhages (bleedings) are present in the heart.

- The liver is swollen and friable and some congestion of the intestinal mucosa may be present.

- The appearances of the kidneys can be quite characteristic. In a fresh carcass they appear swollen and pale, but after a few hours they soften more rapidly than normal, giving the disease its name.

In lambs the circumstances of sudden convulsive death in the best conditioned lambs, together with the post mortem findings are usually sufficient to be diagnostic.

Smears of intestinal contents may reveal many short, thick gram positive rods. Confirmation requires the demonstration of epsilon toxin in the small intestinal fluid. Fluid, not ingesta, should be collected in a sterile vial, within a few hours after death and sent refrigerated to the lab for toxin identification. Chloroform added at 1 drop for each 10mls of intestinal fluid will stabilize any toxin present.

Control and Prevention

There are two main control measures available:

- Reduction in the food intake. Moving lambs from a lush pasture to a poorer one may help to minimize losses, and similarly avoidance of any sudden changes in diet which are likely to result in acidosis and promote conditions favourable to multiplication of the organism and production of toxin.

- Vaccination: Ewe immunization is probably the most satisfactory method of control. Breeding ewes should be given 2 injections of Type D Toxoid in their first year and 1 injection 4 - 6 weeks before lambing each year thereafter. Lambs should receive their first vaccination dose when 8 - 12 weeks old and a second dose 4 - 6 weeks later.

Polyvalent vaccines protecting against other clostridial diseases such as Blackquarter, and Tetanus, frequently incorporate components protection against Lamb Dysentery and Pulpy Kidney Disease, and the manufacturers' instructions should be closely adhered to.

Pest of Small Ruminants (PPR)

Introduction

Peste des Petits Ruminants, otherwise known as Goat Plague or Pseudo-rinderpest, is an acute or subacute viral disease of goats and sheep characterized by fever, erosions and inflammation in the mouth, lips and tongue, gastroenteritis, pneumonia and death.

Goats are primarily affected, sheep less so and cattle are only sub-clinically affected. Humans are not at risk.

This is a disease which occurs mainly in the Sahel region of Africa, that area to the south of the Sahara; and the Middle East, to which it was introduced via large importations of goats and sheep from Africa.

A recent outbreak in north-west Kenya , entering via the Sudan , devastated many flocks of goats and sheep, which, not having encountered the disease before, suffered very high mortality.

Cause

The virus responsible is a member of the Morbillivirus genus of the Paramyxoviridae family. It shares antigens with other members of the genus. The virus of Peste des Petits Ruminants and that of Rinderpest partially cross protect. As Rinderpest has now been eradicated this fact is now of academic interest only.

Nomadic goats and sheep in the Sahel have a high innate resistance to PPR and usually undergo subacute reactions.

Mode of Spread

This is by close contact. Confinement favours outbreaks.

Secretions and excretions from sick animals are the sources of infection. New infections are initiated when the virus is inhaled by in-contact goats or sheep. The virus enters the new host through the cells of the upper respiratory tract and the conjunctivae.

Signs of PPR

1. Mortality in goats apart from the nomadic Sahel goat ranges from 77% to 90% and death usually occurs within a week of the onset of the disease.

2. An incubation period of 2-6 days is followed, in the acute form, by a sudden rise in body temperature to 40 - 41.3 degrees C.

3. Affected animals appear ill and restless, have a dull coat, dry muzzle, congested mucous membranes and a depressed appetite.

4. There is a clear nasal discharge which soon becomes filled with pus with an unpleasant smell. There may be sneezing.

5. The discharge from the nose and eyes encrusts the nose and matts the eyelids.

6. Severe destructive inflammation affects the lower lip and gums and the tissues where the lower front teeth are inserted into the gum are also similarly severely affected.

7. In more severe cases it may involve the dental pad, palate, cheeks and their papillae and the tongue.

8. There is intense depression and diarrhoea may be very heavy.

9. There is dehydration, hypothermia, followed by death, usually after 5 - 10 days.

10. Bronchopneumonia (inflammation of the lungs. Lungs develop redness, contain fluids, become heavy, may sink in water - general change in color) with coughing may develop in the latter stages of the disease.

The disease is less severe in sheep and sub-acute reactions are more common than in goats, manifested by nasal catarrh, low grade fever, recurring crops of mucosal erosions and intermittent diarrhoea. Most recover after a course of 10 - 14 days.

PPR may affect the immune system of the animals so that more complications arise. The most common activated complication is pasteurella pneumonia, but other latent infections may also be activated. Orf lesions of the lip, for example, commonly develop in surviving goats.

Diagnosis

The following post-mortem findings in goats and sheep possessing low natural resistance should point the way towards a diagnosis, with confirmation supported by the detection of specific antibodies in lymph nodes and tonsils and the isolation and identification of the causal virus by in cultured blood samples.

- The carcase is dehydrated and soiled with foetid, fluid faeces.

- Muco-purulent discharges encrust the nose and eyes.

- Necrotic lesions are seen inside the lower lip and on the adjacent gum, the inside of the cheeks and on the lower surface of the tongue. The erosions are shallow, with a red, raw base, which later becomes a pinkish white with a sharp edge.

- Severe lesions are frequently seen in the 4th stomach and in the large intestine.

- A prominent post mortem finding is a purulent bronchopneumonia masking an underlying primary viral infection, manifested as areas of level red consolidation.

Diseases with similar symptoms:

Differential diagnosis includes Heartwater, Contagious Caprine Pleuropneumonia, and Nairobi Sheep Disease.

Treatment and Control

There is no specific treatment, which must therefore be symptomatic.

The veterinary authorities must be notified at once of any symptoms in goats and sheep suggestive of PPR, as the disease is not endemic in Kenya . Immediate control by restriction of movement of susceptible animals and vaccination is essential, using an attenuated PPR vaccine. Sick animals should be immediately isolated and contact animals vaccinated. In the event of an outbreak regulation of markets and movement is vital in the mechanics of control.

Rinderpest

Rinderpest has recently been eradicated from the world. However it is important for farmers to be aware of this devastating disease, along with others of a similar nature such as Peste des Petits Ruminants which is caused by a virus closely related to the one that causes Rinderpest.

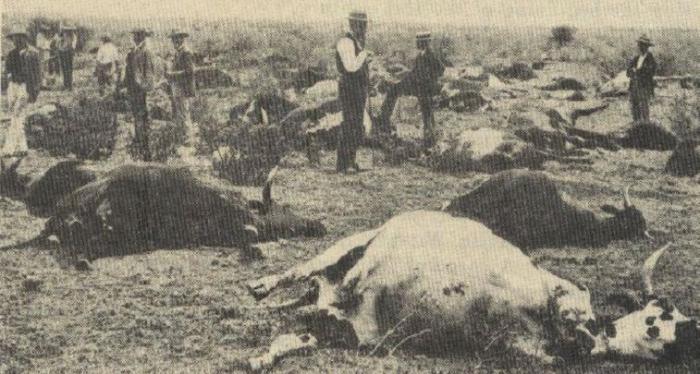

Rinderpest is a disease of cloven-hoofed animals, characterized by fever, erosions in the mouth, irritation, pain and swelling of the mucous membrane of the stomach and intestines, a foul odour, dehydration and death. In epidemic form it is/was the most deadly plague known in cattle. When the disease entered north-east Africa at the end of the 19th century it devastated the cattle and ruminant wildlife from Somalia to South Africa, killing millions of animals as it spread.

All cloven-hoofed animals are probably susceptible, but cattle, buffalo, giraffe, wild pigs and various species of antelope are/were most often affected.

The virus is closely related to that of Measles, Canine Distemper and Peste des Petits Ruminants of sheep and goats.

|

| Rinderpest in the past - now eradicated. |

|

© Dr. Hugh Cran, Nakuru, Kenya

|

Mode of spread

Transmission is by contact, the virus being passed from sick to healthy animals in the air they breathe out, in nasal and oral discharges and in the faeces. Infected droplets are inhaled and the virus penetrates through the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract. There is no carrier state and the virus maintains itself by continual transmission among at-risk animals.

Signs of Rinderpest

- An incubation period of 3-15 days is followed by a fever, loss of appetite, depression, and a discharge from the eyes and nose.

- Within 2-3 days, pinpoint decaying wounds appear on the gums. These soon enlarge to become cheesy plaques affecting the gums, inside of the lips and tongue, and often also the roof of the mouth.

- The discharges from the nose and eyes have mucous and pus and smell foul, and the muzzle appears dry and cracked.

- The final clinical sign is profuse diarrhoea with an offensive smell, often containing mucous, blood and shreds of mucous membranes. There are signs of abdominal pain, sunken eyes, straining, dehydration, general weakness, collapse and death.

- In epidemic areas the number of animals affected was often 100% and the death rate up to 90%.

- Post-mortem signs of decay and erosion are seen throughout the gastro-intestinal and upper respiratory tract with classic "zebra-striping" in the rectum.

Diseases with similar symptoms

The two diseases with which Rinderpest might be confused are the fatal Mucosal Disease syndrome of Bovine Viral Diarrhoea (see above) of cattle and Peste des Petits Ruminants (see above) in goats and sheep.

Prevention - Control - Treatment

Thanks to the development of highly effective vaccines, large scale vaccination campaigns and national and continental control and eradication strategies this devastating animal disease has vanished into the history books. Its elimination should serve as a shining example of what can be done when veterinary science and international political will join forces.

Review Process

1. Draft By William Ayako, Aug - Dec 2009

2. Review by Hugh Cran March 2010 - Jan 2011

3. Review workshop team. Nov 2 - 5, 2010

4. Addition of Pest of small Ruminants By Dr Hugh Cran Oct 2011

- For Infonet: Anne, Dr Hugh Cran

- For KARI: Dr Mario Younan KARI/KASAL, William Ayako - Animal scientist, KARI Naivasha

- For DVS: Dr Josphat Muema - Dvo Isiolo, Dr Charity Nguyo - Kabete Extension Division, Mr Patrick Muthui - Senior Livestock Health Assistant Isiolo, Ms Emmah Njeri Njoroge - Senior Livestock Health Assistant Machakos

- Pastoralists: Dr Ezra Saitoti Kotonto - Private practitioner, Abdi Gollo H.O.D. Segera Ranch

- Farmers: Benson Chege Kuria and Francis Maina Gilgil and John Mutisya Machakos

- Language and format: Carol Gachiengo

Information Source Links

- Barber, J., Wood, D.J. (1976) Livestock management for East Africa: Edwar Arnold (Publishers) Ltd 25 Hill Street London WIX 8LL

- Blood, D.C., Radostits, O.M. and Henderson, J.A. (1983) Veterinary Medicine - A textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Goats and Horses. Sixth Edition - Bailliere Tindall London. ISBN: 0702012866

- Blowey, R.W. (1986). A Veterinary book for dairy farmers: Farming press limited Wharfedale road, Ipswich, Suffolk IPI 4LG

- FAO Rome 1968: Emerging Diseases of Animals. The Enterotoxaemias of Sheep caused by organisms of the Welch Group

- Force, B. (1999). Where there is no Vet. CTA, Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 978-0333-58899-4.

- Hall, H.T.B. (1985). Diseases and parasites of Livestock in the tropics. Second Edition. Longman Group UK. ISBN 0582775140

- Hunter, A. (1996). Animal health: General principles. Volume 1 (Tropical Agriculturalist) - Macmillan Education Press. ISBN: 0333612027

- Hunter, A. (1996). Animal health: Specific Diseases. Volume 2 (Tropical Agriculturalist) - Macmillan Education Press. ISBN:0-333-57360-9

- ITDG and IIRR (1996). Ethnoveterinary medicine in Kenya: A field manual of traditional animal health care practices. Intermediate Technology Development Group and International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Nairobi, Kenya. ISBN 9966-9606-2-7.

- Khan CM and Line S (2005): The Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th Edition, Merck & Co Inc Whitehouse Station NJ USA

- Martin WB (Editor)1983: Diseases of Sheep. Blackwell Scientific Publications ISBN 0-632 -01008 -8

- Mugera, Bwangamoi & Wandera 1979: Diseases of Cattle in Tropical Africa. Kenya Literature Bureau Nairobi

- Onderstepoort Henning 1956: Animal Diseases in South Africa 3rd Edition

- Pagot, J. (1992). Animal Production in the Tropics and Subtropics. MacMillan Education Limited London

- Poisoning in Veterinary Practice Prof. E GC Clarke The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry 106 Regent Street London WIR 6DD 1975

- Sewell MMH and Brocklesby DW (editors)(1990): Handbook on Animal Diseases in the Tropics, 4th Edition 1990. Balliere and Tindall, 24-28 Oval Road, London NW1 7DX, UK. ISBN NO: 0-7020-1502-4

- Sewell and Brocklesby, Editors 1990: Handbook on Animal Diseases in the Tropics 4th Edition. Bailliere Tindall ISBN 0-7020-1502-4

- The African Veterinary Handbook Mackenzie & Simpson 1964 Pitman, Nairobi

- The Merck Veterinary Manual 9th Edition Kahn & Line 2005 ISBN 0-911910-50-6

- The Organic Farmer magazine No. 50 July 2009

- The Organic Farmer magazine No. 51 August 2009

- Veterinary Medicine A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses 1983 6th Edition Blood, Radostits and Henderson ELSB & Bailliere Tindall ISBN 0-7020-0988-1